Making Sense of Jean Beaudrillard's 'Simulation and Simulacra'

I recently finished reading “Simulation and Simulacra” by Jean Baudrillard. It has been part of a process of reengaging with postmodernism and taking it seriously. Now that I’ve become more and more disillusioned with science, liberal capitalism, and notions like truth, justice, and freedom, I was much more receptive to the ideas in “Simulation” and able to read it without a kneejerk reaction. That is not the same as agreeing with everything in it, but only a statement of my ability to take it seriously to begin with.

That being said, postmodernism has a reputation for being, at best, obtuse and dense, and at worst, a meaningless and incomprehensible mash of word salad. After reading Baudrillard, some Derrida, and a smattering of Foucault, I feel like that is only partly true. While it can be difficult to make sense of their writing, that is often intended, and if you make an effort to take seriously what they are saying and understand why they adopt a certain style, the writing will become much clearer.

First of all, most postmodern writers are writing in a tradition of continental European philosophy that has been heavily influenced by literary developments in the 20th century. So it is natural for them to adopt a writing style that attempts to be aesthetically pleasing, or mimics literary currents. My interpretation is that the style often serves to prepare the reader for the ideas contained in the text – by being so unlike traditional philosophical language, postmodern philosophical writing “shocks” the mind into adopting a different approach with the text, one that underscores how it represents a break with philosophical tradition while still being continuous with writers such as Husserl and Heidegger.

I am not so sure whether Beaudrillard is the best introduction to postmodernism. On the one hand, he is the most postmodern thinker I have read, and one of the few who accepts the label, but I also feel he goes beyond postmodernism into something else, something much more frightening, that we are still only in the early stages of. However, the concepts of simulation and simulacra are similar to the idea of repetition found in Derrida, and there are other parallels between Baudrillard and other thinkers. In general, Baudrillard is less philosophical, and more of a cultural critic. Most of his examples are drawn from culture, recent history, and politics.

If you sit down to read Beaudrillard, you will be greeted by paragraphs such as the following:

In this passage to a space whose curvature is no longer that of the real, nor of truth, the age of simulation thus begins with a liquidation of all referentials - worse: by their art)ficial resurrection in systems of signs, which are a more ductile material than meaning, in that they lend themselves to all systems of equivalence, all binary oppositions and all combinatory algebra. It is no longer a question of imitation, nor of reduplication, nor even of parody. It is rather a question of substituting signs of the real for the real itself; that is, an operation to deter every real process by its operational double, a metastable, programmatic, perfect descriptive machine which provides all the signs of the real and short-circuits all its vicissitudes. Never again will the real have to be produced: this is the vital function of the model in a system of death, or rather of anticipated resurrection which no longer leaves any chance even in the event of death. A hyperreal henceforth sheltered from the imaginary, and from any distinction between the real and the imaginary, leaving room only for the orbital recurrence of models and the simulated generation of difference.

This probably seems like gibberish to you unless you’ve already read a lot. What I hope to do with this post is try to demistify it, and hopefully show to you that there is some content of value in “Simulation and Simulacra.” To begin with, we should look for neologisms that express concepts in Beaudrillard’s philosophical or cultural theory. Two that come up from this paragraph are “the real” and “hyperreal.” I will talk about “hyperreal” later, after describing the stages of simulation and the definition of simulacra. First, let’s look at “the real.” You might expect something like “reality” to be used here, but it’s possible that Beaudrillard was referring to pre-existing philosophy and psychology in his usage of “the real.”

In the psychoanalytic and philosophical theory of Jacques Lacan, the Real (note the capitalization) is one of the three registers, a framework through which Lacan performs his analysis. It is defined in negative terms, as that which lies beyond the paired Imaginary-Symbolic registers, and it appears to me to be akin to Kant’s ding-an-sich, the thing-in-itself that is not accessible to experience. I think taking it this way is OK for understanding Beaudrillard, as the exact nature of the real isn’t important to his thought, only its presence or absence. And what Beaudrillard has to say about its absence is the key point of “Simulation and Simulcra.” The whole book is dedicated to showing that where the real once was, it no longer is.

The Four Stages of Simulation, according to Baudrillard.

In the second section, titled “The Divine Irreference of Images,” Beaudrillard does something helpful for once and defines simulation: “To simulate is to feign to have what one hasn’t… to simulate is not simply to feign.” What he means by this is that when you simulate something, you are pretending that the simulation is the thing you’re simulating, and in a way that makes the simulation take on aspects of the real thing. He describes simulation as threatening the difference between true and false, and between real and imaginary. Now let us ask ourselves a question. What happens when simulation becomes indistinguishable from reality? According to Beadurillard, reality itself is erased, replaced by the simulation that became more real than reality itself. This is what he calls “hyperreal.”

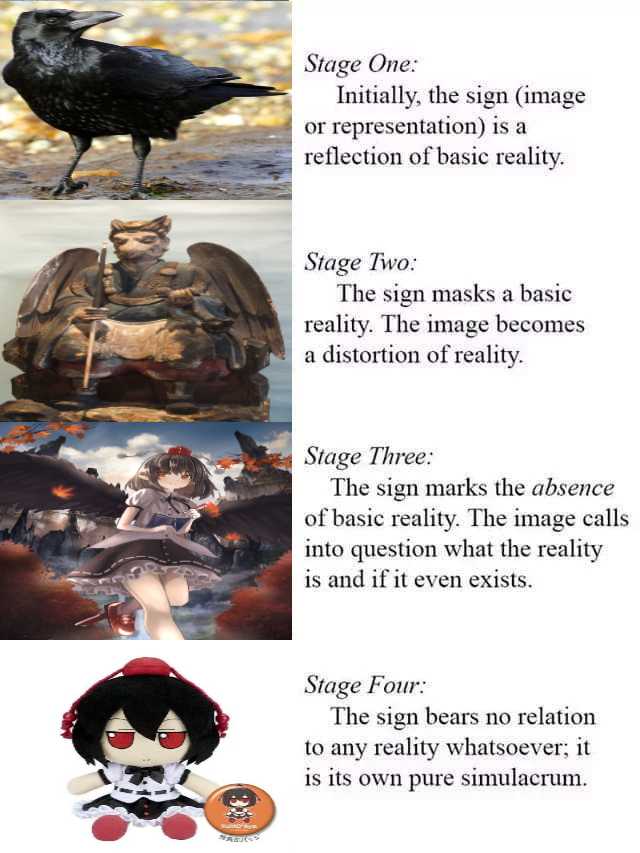

Beaudrillard describes simulation as proceeding in four stages:

- It is the reflection of a basic reality.

- It masks and perverts a basic reality.

- It masks the absence of a basic reality.

- It bears no relation to any reality whatever: it is its own pure simulacrum.

In the first two stages, the real still exists. At first, the simulation is simply taken as a reflection of reality, a mirror. In the second stage, reality exists, but is confused with the simulation. The simulation is a distortion of reality, one that threatens to overtake it. By the third stage, the real no longer exists. The simulation itself draws attention to the absence of reality, but is still related to the reality that once existed. The relationship between the simulation and the original reality is severed in the fourth stage. The image or object produced by the simulation is its own simulacrum. If you look up “simulacrum” in a dictionary, one of the definitions you’ll get will be something like “an unsatisfactory imitation or substitute.” Beaudrillard would disagree with this. For him, a simulacrum is not merely an imitation or a substitute. It is more real than reality itself, and in the act of producing it, reality vanishes.

To summarize, let us go through the process again. Simulation seeks to reflect or recreate reality, but by repeating the act of simulation, what we create becomes closer and closer to reality, to the point that it overtakes reality. At this point, reality vanishes; we can no longer speak of any “real” outside of the simulation. Eventually, even the idea of the simulation being related to a no-longer-existent reality fades, and we are left with a simulacrum. This simulacrum is more than real, hence the term “hyperreal.”

I’ve covered only the first few sections of “Simulation and Simulacra,” but they are the most important. These introduce the basic problems and concepts that Beaudrillard uses through the rest of the book to analyze contemporary (at the time of writing, the 1980s) social and cultural trends. If you want to have a stab at reading it now, I suggest reading everything up to the start of the section “Hyperreal and Imaginary.” That will get you everything I covered in this post.

I don’t know if I’ll consider my exploration of Beaudrillard as a series. If I do, rather than go through the entire book “Simulation and Simulacra,” I’d rather take some of the examples he uses and modernize them, to make them more understandable for an audience who didn’t grow up in the 1960s and 70s.